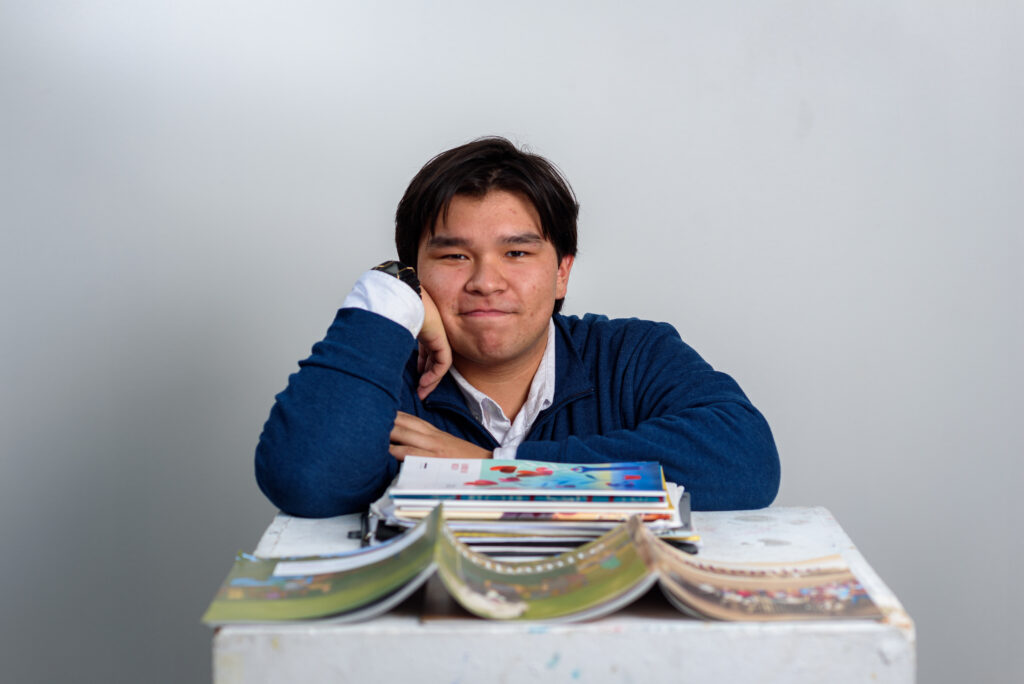

Jason Clark endured an undiagnosed brain injury, homelessness and alcoholism before becoming a 2016 M.A.T. graduate and transforming his life.

Jason Clark walked along Airport Road toward Richmond. In town, he might find some food to eat or friends to hang out with. This had been his commute, so to speak, for the last year and a half, ever since he spent his nights in a forgotten shed in the country, hidden in a copse of trees amid farm fields, chasing away thoughts of suicide with alcohol.

Other than the shed, Clark had run out of options for places to stay. He had been evicted from his apartment. He then slept in his car, but it had been repoed. He wasn’t going to press his luck with family members, not anymore. His life as an alcoholic had worn out his welcome. No one had kicked him out, but he knew when it was time to move on.

As he walked to town, Clark saw a pickup truck draw closer and slow down. He recognized the men inside, two Vietnam War veterans who would hang out at the VFW Post in Richmond. Clark was an Iraq War veteran himself.

“Fancy seeing you here,” the driver said, as if it were all some lovely accident.

They asked if he needed a lift—they’d get lunch together too. Clark took them up on it, sliding behind the passenger’s seat to the back of the truck cab.

Clark explained that he had just been out for a walk, but the men knew better. Actually, none of the truck-cab pleasantries were the truth. Not from anyone.

When the truck got to I-70 and made its way to Indianapolis, Clark asked where they were going. Richmond was the other way.

“Turns out they had staked out the road to find me,” said Clark. They didn’t know where exactly he slept at night, but they knew he had been spotted on that road and that he needed help. Clark was furious, but there was little he could do.

After Airport Road

Life improved after the abduction. The men took him to the Veteran’s Administration office in Indianapolis that day, explaining that he could get the benefits he was due. Clark was owed disability compensation for a previously undiagnosed traumatic brain injury, the result of his tour as a Humvee gunner in Iraq from 2005-2006.

His patrols regularly traveled a highway known as “the most dangerous road in the world,” a reputation gained from a seemingly unending supply of improvised explosive devices and ambushes. Over the year he was in-country, there were nine direct IED hits on his Humvee, seven of those in a three-month period alone. He was always okay, or so he thought. After each, he’d scramble to focus on the security of his team. He had all his limbs so, as he figured, he was good to go. He didn’t connect the headaches he had with the explosions he survived. It didn’t, however, take long for the doctors in Indianapolis to make the connection.

But once Clark had his first big check for compensation backpay, he had another problem. “Here was this life-changing check, and I couldn’t cash it because I was blacklisted from previous accounts,” said Clark. A sympathetic banker finally heard him out and agreed to create an account for him, but only if he agreed to clear his debts. He went into the bank every day and made calls and arrangements to pay off what he owed. After a year and a half of living in the shed, he could now get back to living in an apartment.

Looking back, Clark can see that walk along Airport Road and the kindness of a banker as hinge points for his life, moments when others had reached out to help him. As he began to put his life together, he didn’t know exactly which kind of job he wanted to do for a career, but he knew he didn’t just want to get by and survive.

He had a gift for connecting with people and a heart for helping them. Education was one of the careers he considered, but stuck with it only for a semester while going to Indiana University East. Instead, he studied history there and plugged away with determination if not yet with a greater purpose in mind. He approached classes like they were his job, driving to campus at nine in the morning and not leaving until four or five.

He even tried different college activities, including cheerleading and club rugby, although the latter may not have been his wisest choice. “Someone with head trauma probably shouldn’t play rugby,” Clark admitted with a laugh.

Assessments continued at the VA to better understand the extent of his traumatic brain injury. He had even begun undergoing some therapy. The focus on school and activities helped, and it became a time of stability.

The teacher within

After a friend told him about Earlham’s Master of Arts in Teaching program, he reconsidered making teaching his vocation.

Earlham brought its own learning curve. Clark had grown up in Richmond and Wayne County, so he knew about the College, but it wasn’t, in many ways, familiar. “I had the idea that Earlham’s that weird fancy place over on the west side,” said Clark.

“At this point in my life, I had not really discovered who I was,” said Clark. “I had taken classes in college to move on to what was next. At Earlham and in the M.A.T. program it’s different. It’s Socratic. You’re going to talk about important issues, collaborate and you’re going to reflect on personal things.”

Clark was leery of this approach to learning and the level of self-understanding that was called for. Besides his dark days after serving in the Army, his childhood and family life had also been tumultuous. His elementary school days, for example, included 13 different schools. Then there was a stretch in 7th grade when his mother left him at home for two months by himself. He went to school just so he could eat lunch.

“I was like, ‘Hold on, you want me to admit that I’m afraid of something? I can’t—I can’t do that.’ I had shoved things down for survival purposes. And that’s where the M.A.T. program helped me. I had been living for myself. There was still that part of me that was closed off inside. So, there I was, 31 years old and just starting to think about what kind of person I want to be. What I learned was that I needed to, as they say, ‘awaken the teacher within.’ That’s where my happiness was going to come from.”

On a mission

The process of reflecting on his own serious struggles helped him to picture the teacher he wanted to be, and more. “When you start to look at what kind of teacher you want to be, you start to kind of figure out what kind of person you want to be.”

Clark worked for two years at Richmond Public Schools before taking VA positions to help veterans for a few years in Kansas, Iowa and Missouri. He has a fiancée now, and he’s headed back to teaching in Indiana, probably in the Indianapolis area.

“It’s teaching that I missed,” said Clark. It’s where he saw his students bloom and had an impact on their lives. “I still get texts from students from years ago who want to know if I’ll come to their gymnastics meet or something.”

As he talks about teaching, his sense of mission and his approach to teaching becomes obvious. Earlham’s M.A.T. program taught him to be a professional educator, one who educates the entire child and makes sure that all students, not just the fortunate ones, have the ability to learn.

Growth is what he wants to see in the kids he teaches. Where they start from is not something he can change, but he can make sure they are able to take the next step. He still has fears, but they have more to do with not reaching students. He doesn’t want to let them down.

“Have I done everything I can to serve them? Have I understood them as students?” he asks himself.

Teaching has also had an impact on his personal and professional growth.

One of his most memorable moments as a teacher came just two weeks into his first teaching job. He remembers correcting a boy in his class on some behavior. Nothing major, but both Clark and the boy dug in.

“I was arguing with an eighth grader and not being the grown man in the room,” said Clark. “And I ended up kicking him out and wrote him up. Planned to call his mom about it the next day.”

After some hours away from the incident, Clark began to think differently.

“I reflected on the situation, and I credit the M.A.T. program for that.” Clark said.

Clark realized that he didn’t handle the situation well. He had made it about control, as he recalls. The next day, he spoke with the boy in the school hallway: “Hey, man, that was on me. I’m sorry.” Instead of calling the mother of the boy to complain, he explained that it was his fault the issue escalated.

“That was a turning point for me,” said Clark. “I made a choice about what kind of teacher I want to be. It was more important to build a relationship than control things.

“And it worked out well. I never had a problem with that student ever again. He actually became like my classroom ‘enforcer.’ If other kids started to do something, he would be the one to tell them, ‘Hey, man, we don’t do that here.’”

Clark knows the power of someone looking out for him, of someone being there for him even when he wasn’t much inclined to help himself. He wants to be there for others.

“A lot of your best days teaching come from being a safe harbor. Some of the kids I’ve worked with have been on their second or third or fourth chance or whatever. I want to make sure I am there for them—because that’s what people have done with me. It was like when I was taken to the VA. I was just a stubborn idiot at that time. But they explained things to me, they made it relevant to me, and that just opened the door to everything. That’s what I want to do—be there for students.”

“A lot of your best days teaching come from being a safe harbor. Some of the kids I’ve worked with have been on their second or third or fourth chance or whatever. I want to make sure I am there for them—because that’s what people have done with me. It was like when I was taken to the VA. I was just a stubborn idiot at that time. But they explained things to me, they made it relevant to me, and that just opened the door to everything. That’s what I want to do—be there for students.”

Jason Clark

Story and photo by Dan Oetting