Curious moments from Earlham’s first 175 years.

To help celebrate the 175th anniversary of Earlham, we’ve gathered some of the odd and fun moments from its history—a grab bag of shenanigans, interesting bits and things that might make you blink and say, “Oh, really?”

And in 175 years, you can expect some oddities—and more than a little nonsense, certainly more than an article like this can hold. There are stories yet to be told of a cow let loose in Carpenter, bats put down the chimney in Runyan, “Welcome to Oberlin” signs appearing on campus, cars being wedged between trees and inside buildings, a student’s dorm room contents relocated to the bathroom or the middle of The Heart. Even just this May, the Adirondack chairs from The Heart mysteriously found their way atop the front portico of Earlham Hall and to the farthest reaches of the Athletics and Wellness Center tower.

May Day

If not for the library

The May Day celebration at Earlham was born in a library reading room. The first May Day took place in 1875 thanks to Lizzie and Harriett Foulke, sisters who were inspired to establish an Earlham May Day after reading the May 23, 1874, copy of Harper’s Weekly about Old English May Day. As reported in Richmond’s Palladium-Item newspaper, the sisters “were intrigued by accounts of England’s May Day festivities and were seized with a desire to introduce the custom into our over-serious America, as they regarded her.” The tradition of holding a big May Day celebration every four years and a smaller May Day festival in the other years lasted at Earlham until 1993.

No going home

Because of a major flu outbreak in the U.S., students at Earlham were kept from going home for Thanksgiving in 1918. As a consolation, the administration an-nounced that Christmas break would be lengthened by a week. In February of 1919, the flu hit the campus especially hard. Fifty people, including four members of faculty and staff, were afflicted and two weeks of quarantine restrictions were put in place for the College. Twice-a-day temperature checks were done of all students, and any that developed symptoms were observed further and immediately segregated. Four cases were severe enough to develop pneumonia.

The darkest sunny day

At 1:47 p.m. on Saturday, April 6, 1968, as many seniors were taking their GREs in Tyler Hall for graduate school, a gas main exploded near a gun store in downtown Richmond, which set off gunpowder. Several blocks of the city were decimated by the blast, and a total of 41 people died as a result. Students from Earlham assisted with the immediate clean-up. In the week that followed, the Earlham Post reported on the gratitude of the mayor, Byron E. Klute: “ The Earlham kids were just tremendous,” Mayor Klute said. “ They cleaned up all of City Hall and there must have been 35 kids sweeping from Fourth to Fifth Street. The work they got involved in was significant and needed. We got back into City Hall and started work and the glass they cleared off the streets was a real hazard.”

Earlham’s Elsa

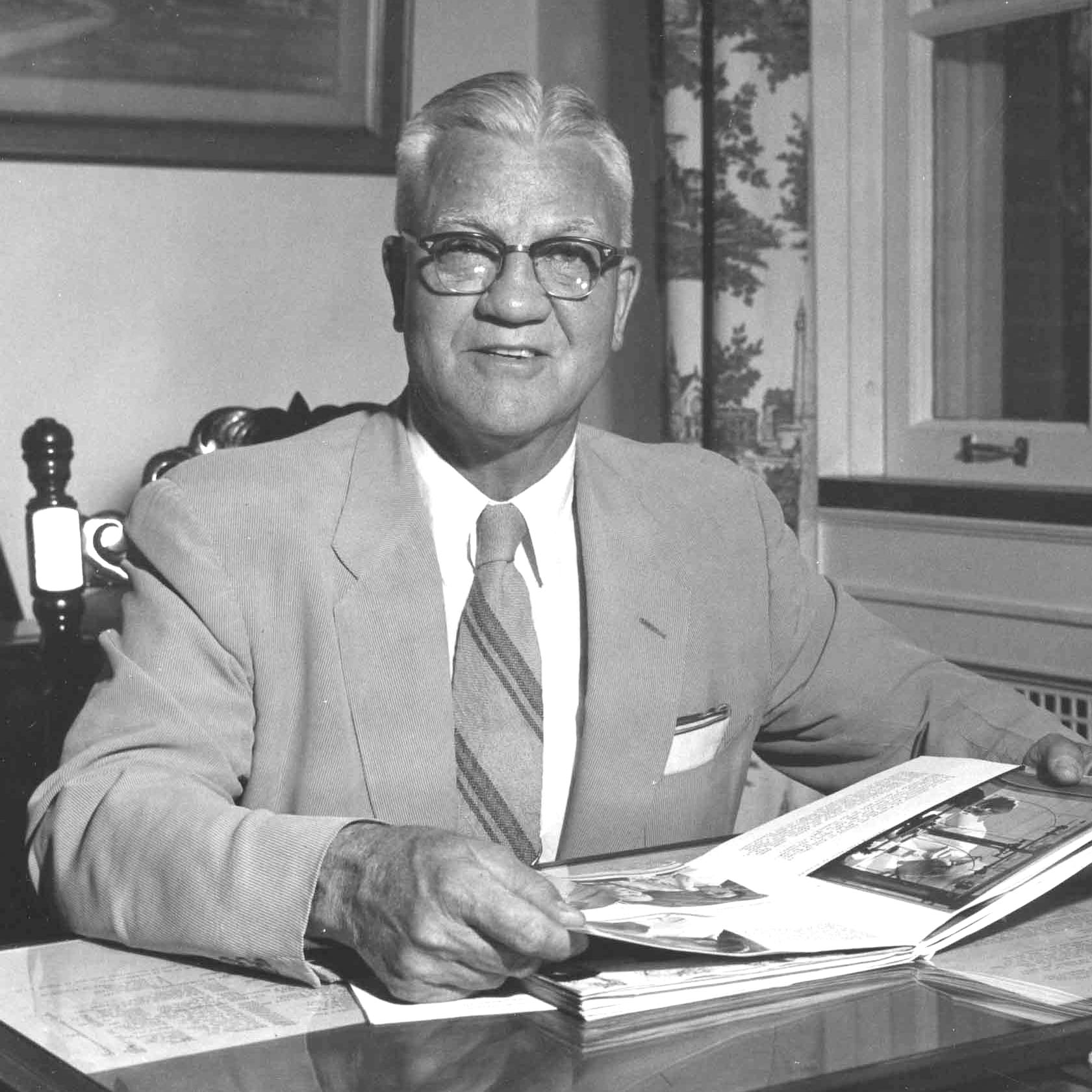

Tom Jones ’38, was president of Earlham from 1946 to 1958. His given name was Elsa Jones, but when he originally entered Earlham as a student and was assigned to Earlham Hall, then the women’s dorm, he figured it was time for a new name. He took Tom from his mother’s maiden name of Thomas.

The grass is greener

Front campus was originally farmed. In 1912 alfalfa re-placed potatoes on the west side. The grass of the present day followed not too long after.

Snowballs for peace

The snowball fights between the residents of French House and German House were intensifying during the winter of 1974-75, leading to German House declar-ing war and proceeding to capture a French House man and make him eat tea and cookies with them. Entreaties from the houses were made to both the president of Earlham and the provost. Aiming for a peaceful resolution, the president and provost proposed a snowball duel between the two admin-istrators, who would serve as proxies for the two warring houses. The two men met on The Heart and stood back to back. After taking twenty paces each, they turned to unleash their snowballs—at which point, they realized they were now too far apart. They agreed to both move 10 steps toward each other and then commence throwing snowballs. No word remains on who won, but the event apparently managed to satisfy the honor and need for silliness of both sides.

Twice at Earlham, but never as a serving president

Herbert Hoover, the Secretary of Commerce in the Harding administration, gave an address titled “Service” at the College’s 1922 May Day celebrations. Hoover began his presidency seven years later. He grew up as a Quaker and had family ties to David Hoover, one of the founders of Richmond. Hoover would return to Earlham in June of 1939, after his presidency had ended, to speak at Earlham’s graduation day.

An accidental protest

The students at an assembly in Goddard Auditorium in March of 1949 knew the topic of the day, pacifism, was an important one. Though most male classmates of theirs had registered for the draft, there were some who refused on principle—and well understood that they would be arrested for that decision. It was an issue that caused some chafing between classmates and even between Earlham and the Richmond community. For the assembly, the administration invited two speakers, one to give the case for pacifism and Col. Melvin Maas, president of the Marine Corps Reserve Officers Association, to make a case against it. Maas took his turn at the podium after a vigorous case for pacifism was made and he made it to the halfway point in his speech when a dead cat dropped down within a few feet of the Colonel’s head. Obviously, this was done in protest, right? Except it wasn’t. Alana Pryor Ackerman ’05 researched the prank and wrote about it in the EarlhamWord in 2003. She explained that the cat had been borrowed from the Biology Department and was attached to an alarm clock mechanism which, when the alarm went off, lowered the cat on a string. What appeared to be a protest of a particular point of view, however, was a misfired prank. The descending cat was intended to disrupt the meeting of a campus literary group dedicated to creative writing called Ye Anglican, which was originally scheduled to use the stage at the time. When the four men responsible learned about the schedule change, they attempted to dismantle the cat-dropping apparatus, but the line wouldn’t budge and they were unable to remove it in its entirety. They assumed it was stuck and that there was nothing to worry about. Except it worked perfectly. The Colonel took it in stride, according to Ackerman. As the cat dangled, Maas paused only to say, “Well, at least somebody fell for my speech.” The Colonel went on to receive a standing ovation. The four pranksters, on the other hand, found justice. Or, rather, they went looking for it. The four students wrote a public letter of apology that shared their regret and explained that their plan had been to prank only fellow students. They asked for and were granted a suspension of several weeks. President Tom Jones is quoted in the Indianapolis News as saying that the “actions of the four students, in asking suspension for atonement for the prank is an excellent example of what we at Earlham call ‘freedom under responsibility.’ [We] are gratified that the students had the courage to admit their mistake.”

Pie of ignominy

In April 2005, journalist William Kristol gave a speech in Goddard Hall to students and guests. At about the 30 minute-mark a student mount-ed the stage and threw a pie at him and then ran away. President Doug Bennett also took some of the pie damage as he stood to defend Kristol. Kristol took a moment to wipe away some of the pie from himself and then continued his speech to a conclusion a few minutes later. The audience gave him a standing ovation and again rose to their feet after Kristol’s Q & A session and as Bennett thanked him for a final time. Earlham’s faculty condemned the action in a subsequent meeting, issuing a statement to that effect. Meanwhile the incident was reported in the New York Times and elsewhere across the U.S. The pieing was intended as a protest against Kristol’s support for the Iraq War.

THE GRAND DETOUR

Perhaps one of the biggest pranks that ever took place at Earlham happened in the fall of 1951, when eastbound U.S. Highway 40 was rerouted through campus. (Interstate 70 wouldn’t be completed until 1956, so U.S. 40 was a key road for trucking.) At that time, the Main Drive extended to Earlham Hall. After making it to Earlham Hall, traffic could then take a left and reach College Ave. and head back to 40. That was the intended route for the elaborate prank, which involved collecting decommissioned highway detour signs for a year and enlisting third parties to put them up. The prank hit a major snag when someone placed a sign incorrectly directing traffic to a route that forced too tight a turn for the semis. Traffic was entirely stopped, and U.S. 40 was backed up until police unsnarled the mess. Meanwhile, the conspiratorial crew that put together the prank were off-campus in places where they knew they would have an alibi, including a few who dined with a member of the Indianapolis Police Department. Once the police remedied the situation, the detour signs were stacked and traffic went back to normal. Normal, that is, until a few other students from Bundy Hall tried to reroute traffic again with the same signs. They took all of the heat for the prank, and the original conspirators of the grand detour were never found out.

Raided by the Feds

Before the campus radio station WECI existed, there was a forerunner called WVOE in the early 1950s. It was a carrier station, meaning that it used the wiring in and between the dorms to produce very low-power AM broadcasts. At least they were supposed to be low power. No one working on the project had much experi-ence with the technology, and the power for the station had been increased enough so that it was knocking out a Cincinnati radio station for much of Richmond. Complaints led to the FCC searching for a rogue station. Two vans with antennas eventually sniffed out the folks behind WVOE, which was located in the base-ment of Bundy Hall. The FCC personnel confronted those operating the station and confiscated some of the equipment.“ They were awfully nice about it,” said the manager of the station at the time, Richard Stadelmann ’54.“ They actually just started laughing when they looked at our equipment. They couldn’t imagine anything so primitive.”

Dressed for success

’79

“Sheik” on the scrape crew, Sargasso, 1979

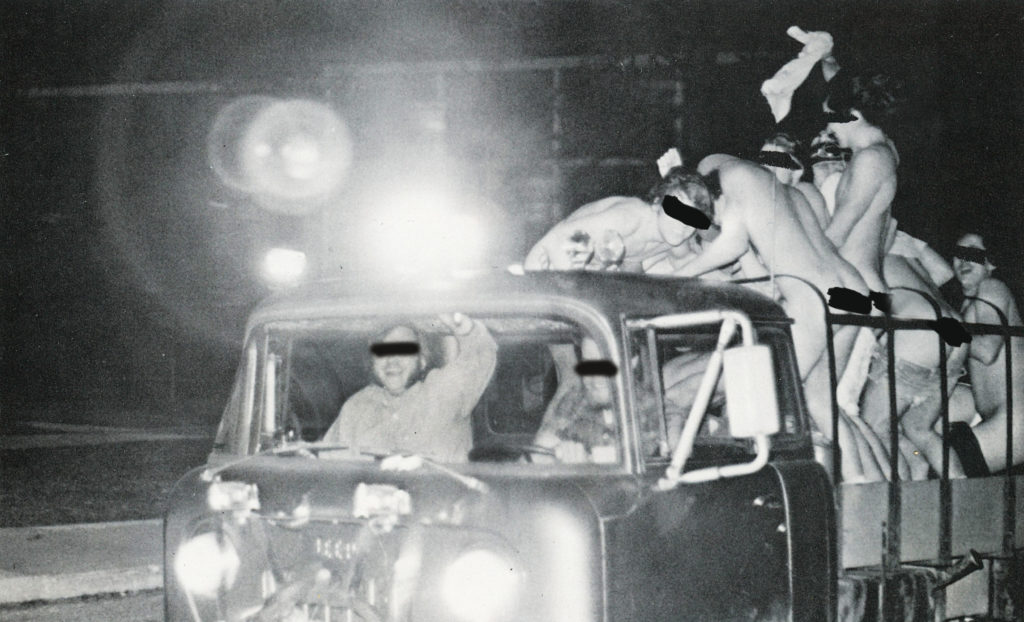

“Are you here to see the streaking show?”

NO SHOW TONIGHT

Streaking—running nude through a public space—was a trend on college campuses in the mid 1970s, and the craze landed at Earlham as well. Several streaking events took place with only the usual on-campus reaction. For one upcoming mass streak-ing event however, word had gotten out in Richmond where and when it would happen on campus. This was a bit more publicity than desired for some Earlhamites. John Carter ’76 addressed the issue by borrowing a friend’s work truck that had a flashing yellow light on top. After dark, he and Jenny Beer ’76 parked along Main Drive, stepping forward and waving their flashlights. “Are you here to see the streaking show? Sorry to say, the show has been canceled tonight.” Every single driver said, “Okay, thanks,” turned around their car and left.

Outbreak

In November of 1957 the flu bug hit 45 percent of the campus, putting a halt to extracurricular events, and the mid-semester grading period was extended by a week. Afflicted men were placed in the Day Dodger lounge in Barrett Hall, spilling out also into the hallway. Women with the flu were sequestered in the infirmary and an Earlham Hall parlor.

The SAGA saga

It’s been a few decades since SAGA was Earlham’s food service provider, but you’ll still hear students referring to the dining hall as SAGA. SAGA served up meals at Earlham from 1965 through the 1980s. Because of its capitalization, SAGA appears to be an acronym, but it was named after a former Native American village called Kanadasaga in upstate New York, near corporate headquarters for SAGA.

Float gone missing

As reported in an October 1962 issue of the Earlham Post, a group of first-year students swiped the sophomore class float and moved it to The Heart, damaging it in the process. Sophomore class president Larry Overman ’65 said that there were no hard feelings—that the float had been stolen in good fun and was only sorry that it had gotten out of hand.

First names, please

The use of first names to address others on campus originated in the 1950s during the administration of President Tom Jones, known to everyone as Tom, a gesture of humility that recognized that there is no hierarchy between the members of humanity in the eyes of God. The Quaker tradition was to use the full name of others for the same reason.

Unified colors

In 1930, maroon and white are selected as the College’s official colors. Prior to this, the College had used gold and white for the academic colors of the school and maroon and white for the athletic colors.

Bundy 500

Students sponsored cockroaches in this annual race that reached its heyday in the 1980s. The event was originally hosted in the basement of Bundy Hall and was moved to the lobby and was carried on closed-circuit TV on campus so that more could watch. A $3.7 million renovation of Bundy, the oldest dorm on campus, was completed in 1995. A writer for the Palladium-Item speculated that the changes to the building would have an effect on the Bundy 500 cockroach race “because insects are scarce in the newly redone building.”

Not your ordinary roaches

In the late 1980s, Marcy Wood ’90 of Louisiana, imported cockroaches from the Bayou region to race in the Bundy 500. Her roaches nearly took all of the spots on the podium in one year and took second and third in the next year. Wood’s father, who also went to Earlham, captured the cockroaches by enticing them with peppermint. Publicity for these cockroach phenoms included stories from the Palladium-Item and Times Picayune of New Orleans. When the Associated Press picked up the story, it ran across the United States.

kicking post

Ancient dating ritual

The Kicking Post has been a fixture at the entrance to campus since the Class of 1940 had it created from one of the window sills of Lindley Hall, which had burned down in 1924. The inscription on it reads,“If there’s a wish within thy heart, To my stone face a kick impart. And, though thee may have stubbed a toe, Upon my word it shall be so!”

Other kicking posts preceded this one however, and, according to Carol Baldwin ’58 they also figured into courtship at Earlham. “In our parents’ day, the kicking post was a telephone pole and it was the custom for a couple to walk down the drive and stand by the pole. Here the boy would kick the post, and the girl, being a knowing young Earlhamite, would understand from this gesture that he wanted a date. Then they would walk hand in hand back up the drive.”

’76

“FOREVER BUNDOS”

Bundy Hall declared its independence on the evening of Oct. 10, 1975. A declaration was sent to the Palladium-Item, Richmond’s mayor and the U.S. Congress. The letter printed in the Pal-Item reads: “We are called upon to notify you of the fact that Bundy Hall, formerly associated with Earlham College, has declared itself independent of Earlham, Richmond, Indiana, and the United States of America. We are awaiting your ambassador. We extend to you our good wishes and fervently hope you will respect our sovereignty.” The mayor did, in fact, stop by to attempt to reason with the residents, but to no avail. Larry DeBoer ’78 recalls that the mayor wore a full colonial costume, perhaps because he was prepared for U.S. Bicentennial celebrations coming in 1976. “We greeted him with trumpets—two trumpet players doing a fanfare on the steps’ said DeBoer. “We gave him a passport written in a blue book, then dropped it on the ground to ‘stamp’ it.” The revolutionaries adopted the motto of “Liberty, Equality, Bundity” and created a T-shirt for their cause that depicted a cockroach. Within a about a week, the group had drawn up a constitutional monarchy, which then led to a king and queen being coronated at a banquet. Not too long after the coronation, however, interventions from other dorms—including salvos of water-balloons and shaving cream pies from Hoerner Hall—and a Bundy-wide dorm meeting brought them back into the campus fold. Not everyone in Bundy was happy with the mess that had been made. What led to the bold declaration of independence? The revolutionaries recall boredom, orneriness and several “sophomores being sophomoric” among the reasons.

A foal is born

In the spring of 1988, the Barn Co-op welcomed an 80-pound foal, a surprise to all. The mare, Jamie Carter, had been declared not pregnant by a veteri-narian, but nature knew better, and the foal was delivered in a back campus field in a mud puddle.

Meetinghouse ghost

In the early 1950s, shortly after Stout Meetinghouse was built in the southwest corner of campus, rumors of a ghost in the new building began making the rounds on campus. Strange lights in the Meetinghouse at night were reported, but there was never a resolution to the mystery. It probably should have been the smell of cooked food that gave away the ghost, or that the philosophy books in Elton Trueblood’s private library were rearranged. A friend of the ghost confessed that it was Prosper Prime Van Meulebrouck III ’55, a student who liked to cook his own meals in the Meetinghouse by flashlight. The “ghost” would go on to become a professor of philosophy.

Story written by Dan Oetting and Christopher Parker ’91, with contributions from Jenny Beer ’76, Richard Stadelmann ’54, Larry DeBoer ’78, Lynette “Lucky” Robinson ’68, Hans Kersten ’86, Alana Pryor Ackerman ’05, Carol Baldwin ’58, Wanda Harvey and J. Ragani Buegel ’89.