Photographers Marcel Pardo Ariza and Liliana Guzmàn have distinct and unique voices in their work. So what do they have in common? The dedication, creativity and community building they learned in college.

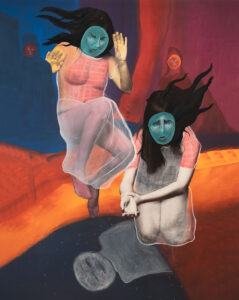

In a New York City gallery hangs an oversized image of a pigtailed young woman crouched in contemplation, a faint pencil-sketch saint’s halo circling her head. Next to her, two blue-faced figures gesticulate dramatically while floating through a star-studded orange void.

In San Francisco, holding watch over a cluster of photos is a portrait of a trans rights activist in a bright red dress and multicolored flower crown standing proudly in front of a wall of googly eyes, as if surrounded by whimsical angel eyes.

These artworks transform the galleries into a riot of color and texture.

The photographs of Marcel Pardo Ariza ‘13 and Liliana Guzmàn ‘16 don’t simply hang on a wall. They meet the viewer with an intensity that insists upon being fully seen and reckoned with. They immerse the viewer in light, color, and texture – frequently the light, color, and texture of another human being’s skin, captured at a scale that is somehow both intimate and larger than life.

While these two emerging artists do not know each other, their combined impact to elevate and celebrate marginalized identities is starting to be recognized, as they further develop the artistic sensibilities they first discovered during their undergraduate years at Earlham College. Ariza, a Colombian-born trans masculine, won the 2004 San Francisco Pride Creativity Award for outstanding artistic contribution to the LGBTQ communities and is working on a new exhibition, set to open next year, focused on uplifting and celebrating trans migrant experiences from the Global South. In response to the current U.S. right-wing anti-trans political movement, Ariza says they want to amplify “the voices of those who transformed to be themselves.”

Guzmàn, who is also Colombian and was raised in the U.S. — she is the daughter of Earlham professor Rudolfo Guzmàn — won the 2023 Rhonda Wilson Award through the Klompching Gallery in New York City. As part of the award, she received feedback from her mentor Debra Klomp Ching as well as from a panel of 19 decision-makers in photography who reviewed her work at FotoFest 2024. Guzmàn is applying the lessons from this feedback to her expressionist mixed-media series Next To Myself, which has been touring in galleries around the country.

Ariza and Guzmàn both draw upon influences from their childhood experiences with Catholic symbolism and ritual, harnessing the traditional iconography of holiness to honor their chosen subjects: self-portraits and depictions of Latinx women for Guzmàn; members of the LGBTQ and trans communities for Ariza. Both artists also intentionally display their works on a grand scale, using gallery spaces in much the same way that churches use large representative art for visual storytelling.

Guzmàn says the larger scale of her prints elevates women’s bodies physically and conceptually: Her photos hang so the viewer is either confronted by them at eye-level or stands slightly below them to experience all of the details of the image. “I wanted to make people really look at these women,” she says.

In 2011, Ariza, who majored in art at Earlham, took a black-and-white photography class with Walt Bistline (who retired in 2023). Students were given an assignment to emulate another artist’s work, and Ariza chose to emulate a queer photographer they admired by photographing a local queer couple. Both the resulting photographs and the process of creating them were transformative. “I really enjoyed creating a level of communal intimacy with the subjects,” they say. “I just love that people were down to create something together.”

Guzmàn similarly discovered the joy of the creative process as a photographer through her early investigations of the artform at Earlham. She first took an Introduction to Photography course through the college’s program for high school students to explore the college experience. She quickly fell in love with the analog processes of film photography – particularly learning to develop her own film in a darkroom. While she spent her childhood documenting her lived experiences through journaling, scrapbooking and drawing, in addition to taking photos and videos, she most strongly gravitated towards photography because, unlike drawing or painting, it provides a “sense of the real world…with an almost tactile quality.”

“Of course you can distort things in photography with lighting, digital editing, things like that,” Guzmàn says, “but essentially, the photograph is a historical document. What’s in front of you is in front of the camera.” At Earlham, encountering the manual processes of working with film photography added another dimension to her appreciation of photography’s “realness”:

“All of these things were so physical and so tactile,” she says, “I really loved that part of photography with a film camera.”

Ariza and Guzmàn built upon this spark of creative discovery throughout the rest of their undergraduate years, not only through deeper exploration of the camera as a powerful tool for expression, storytelling and documentation, but also through studying the humanities. They both cite JoAnn Martin’s courses in the departments of Sociology and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality as having profound impacts on broadening their perspectives.

Ariza was particularly struck by discussions Martin facilitated while teaching post-colonial theory. “We were engaging with deep ideas that to this day are still impacting my creative process,” they say.

Guzmàn was struck by the films shown in Martin’s courses, which impressed upon her the way visual imagery was harnessed by historically significant social movements as a powerful tool for expressive storytelling. Ever since that experience, she has continued to find a wealth of visual inspiration in cinema.

Both Ariza and Guzmàn further broadened their perspectives through faculty-led experiences on- and off-campus.

Guzmàn, who majored in French, says Karim Sagna’s study-abroad program, as well as studying language in general, provided her with rich opportunities to interact with a much wider range of people and the artworks of their respective cultures. “It’s really been this extremely impactful educational base and foundation for who I am as an artist now,” she says, “I’m so thankful that I have that. I just don’t think I could have gotten to make the work that I do without taking all of those different classes, seeing all of those films, reading all of these materials and having discussions with professors and peers.”

While participating in the New York Arts Program, an off-campus opportunity, Ariza bonded with fellow student artist Sucia Urrea over shared experiences, interests and Colombian roots, forging a deeply meaningful friendship that has also led to several creative collaborations over the years.

Ariza says the geography of Earlham’s campus served as a catalyst for both artistic and social experimentation. In contrast to busy cities such as New York and San Francisco, Earlham’s campus lends itself to taking artistic and social risks, they say. In this less urban setting, taking portraits of classmates fostered meaningful connections with many types of people on campus, even if they had nothing in common except where they were in school together. Earlham was also the first place Ariza felt deep validation for their identity as a transman. The faculty support was life-changing, and it empowered them to continue pursuing a life of truly authentic expression.

After graduation, both artists’ journeys have led to creative expansion. Guzmàn deepened her knowledge of technical aspects of photography, such as digital processing, by completing an MFA in photography at Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture + Design, at Indiana University Bloomington where she was entranced by the digital photography lab. While there, she began layering drawing on top of her photographic prints as a way to represent memories and to express the feeling of her memory of a place, instead of a more neutral physical representation. Drawing on photos allowed her to be “a little more poetic” than photography alone could.

Ariza has broadened their creative palette from photographic portraits to developing larger multidisciplinary art installations. “My practice is very rooted in my passion for architecture,” they say, explaining that their motivation to embrace additional art forms stems from photography’s limited command of space. They consider their multidisciplinary art installations to be “expanded images” that allow a single visual concept to fully transform an entire space.

They also shifted from a solo artistic practice to prioritizing collaboration. “Making art in isolation doesn’t motivate me,” says Ariza.

Creating with others is more energizing and is reminiscent of their growing up in a large, multigenerational family. Such creative collaborations have become a vehicle for building a “found family” type of artistic queer community, working alongside others to first get to know them better, and then use public exhibitions of their installations to collectively raise the visibility of all artists involved in the work. That idea extends to include interactive events and activities at exhibitions – particularly to welcome new audiences to art spaces for the first time. Their ultimate goal is to create “an inclusive space…where everyone feels safe and seen, can create something together and is free to fully experience pain and pleasure.”

While Guzmàn maintains a solo artistic practice, she is similarly community-minded in exhibiting her artwork. She mentions that a primary motivation for pursuing exhibitions of her artwork in many different places is to foster opportunities for her to have conversations with visitors to those galleries, and sometimes also offer artmaking workshops to those visitors.

Both artists’ faces light up whenever they speak about connecting with new audiences for the first time. They are excited to keep finding new ways to build those connections and welcome more people into the art spaces that house their works. “I always want my work to feel like a big party,” says Ariza – and everyone is invited.

By Marin Orlosky