Bruce Carter navigated a big life pivot from rock and mineral hunting to film and TV producing.

Avid mineral collector Bruce Carter ’77 has always loved the beauty, mystery and otherworldly strangeness of gems and minerals. The stones’ unique colors, shapes and shine are forged not in the sterile confines of a laboratory but by the earth’s own heat and pressure, which combined with time and a little bit of luck makes something miraculous.

In some ways, Carter’s own life trajectory mirrors the gems he has sought since he was a boy growing up in rural Connecticut – tantalizingly close to the quarries where he looked for treasures such as beryl, tourmaline and garnets. Rather than follow a traditional career path, the geology major’s life has been marked by adventure and serendipity, twists and turns that led him from remote field exploration in places such as the Rocky Mountains and Alaska to the sets and sound stages of Hollywood, where he has worked for nearly 40 years as a film and TV producer.

Although the wilderness of his mineral-seeking youth seems an odd precursor to the sets for productions he has worked on including Benny and Joon, Anaconda, X-Files, Grimm, and Pretty Little Liars, for Carter, his first career smoothly led into his second. His past experiences have given him the tools he needs to be a successful line producer and production manager, roles responsible for managing the day-to-day logistics of a movie or series.

Line producers come with varying approaches and skills, and Carter is one of the best, says David Greenwalt, producer, writer and director for Grimm, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and X-Files.

“The great ones, they solve the problems, and then they don’t tell me about all the problems they solved. They make it work,” he says. “It’s a tough job, and you need to be strong, but it’s also a very diplomatic job. Bruce is absolutely a great creative and line producer, and a man who’s kind of like a chess player. You’ve got to know warfare. You’ve got to know seduction. Bruce has had a life. I like a well-rounded, fully-lived individual. He certainly is that.”

An early passion

When Carter was a young boy, he was fascinated by the cluster of clear quartz that his older sister kept atop her bureau. It wasn’t rare or expensive, as gemstones go, but there was something about it that fired his imagination and triggered a lifelong interest in minerals. He began collecting interesting specimens wherever he could find them: streambeds, rock piles, even a neighbor’s stone walkway before he learned that was not a wise idea. At 14, he had his first exhibit in the town library.

“My passion is minerals, and I’ve been looking for them my entire life,” he says.

Later, he added a second passion: basketball. His skills on the court helped get him accepted to Earlham with a scholarship to boot, although he still has some doubts about how the admissions office made its decision.

“I have an identical twin brother, and he was a National Merit Scholar,” Carter says. “To this day, I think Earlham thought I was him.”

Despite the brotherly imposter syndrome, Carter brought academic strengths to Indiana with his interest in minerals and gemstones. No matter how he got accepted, it was a good fit, at least as soon as he figured out some essential skills.

“It took me two years before I learned how to study,” he says. Even so, he found college to be a place where he could thrive.

“Earlham saved me,” he says. “If I’d gone to a place that was sterner, or expected a fully-grown academic individual, I’d have been doomed. But Earlham was an environment that was just so pure. In my whole four years there, I’m hard pressed to think of a bad social experience. Everybody was so great.”

At work in the field

The summer after graduation, Carter got to work surveying and taking soil and rock samples in eastern Washington state for a uranium exploration company. Other opportunities included mapping energy reserves in New Mexico and logging drill core samples in southern Illinois’ coal country. His shifts were long, the work was hard and soon he decided that he needed to get his master’s degree. So Carter enrolled in the University of Montana in Missoula and later took a summer job with a railroad company doing geologic mapping, a useful skill for a budding geologist.

Three days after his post-thesis party, Carter was in a floatplane heading to an ice-bound lake in the Talkeetna Mountains in southern Alaska where he was part of a small exploration field crew. It was beautiful, rugged country, and he spent three seasons working there. His final season became memorable when an ancient de Havilland Otter seaplane went down after picking up the crew for the return home.

“The crest of the range approached, but just as salvation seemed at hand, with a series of coughs, the engine died,” Carter said in a 2021 article in Rocks & Minerals magazine. “The pilot struggled fruitlessly to restart it… [we] had crested the ridge, but we dropped like a rock.”

The plane plummeted thousands of feet towards the endless green forest and a torrential glacial river far below. The pilot crashed on the river bank, and he, Carter, and the other passenger ran to escape the smoking plane. They spent two and a half days in the backcountry, surviving on a bag of frozen jumbo shrimp.

After that, his passion for wilderness exploration, with its countless hours in little planes and even smaller helicopters, was sated. But his love of minerals continues unabated: Carter still has a collection he’s proud of and serves on the board of directors of the Rice Northwest Museum of Rocks & Minerals in Hillsboro, Oregon.

A different kind of break

Carter’s break into a Hollywood career began as an extra in Ron Howard’s 1986 comedy satire, “Gung Ho.” After that final Alaskan field season, he was working as an English teacher in Argentina when he learned that an American film company was looking for extras who looked like Americans. The producers took note of his ability as an organizer and offered him a job as an extras wrangler in Pittsburgh. He said yes, and with that bid adios to South America and his former life as a field geologist.

And as it turned out, his skills crossed over easily from one field to the next.

Organization, support for a group of people who are moving regularly, air support, food, schedules, all of that was just insanely simple,” he says. “It was a matter of learning new names for the different pieces of equipment, which was actually easier than geology.”

When most people think of Hollywood, they tend to focus on the stars and directors who walk the red carpets and get much of the ink and attention. But Carter’s experience was in the nuts and bolts.

“Counter to everything you read about Hollywood, no other endeavor in the United States is more hierarchical and more demanding of respect for authority. Only the military,” he says. “My Hollywood is the group that makes the show.”

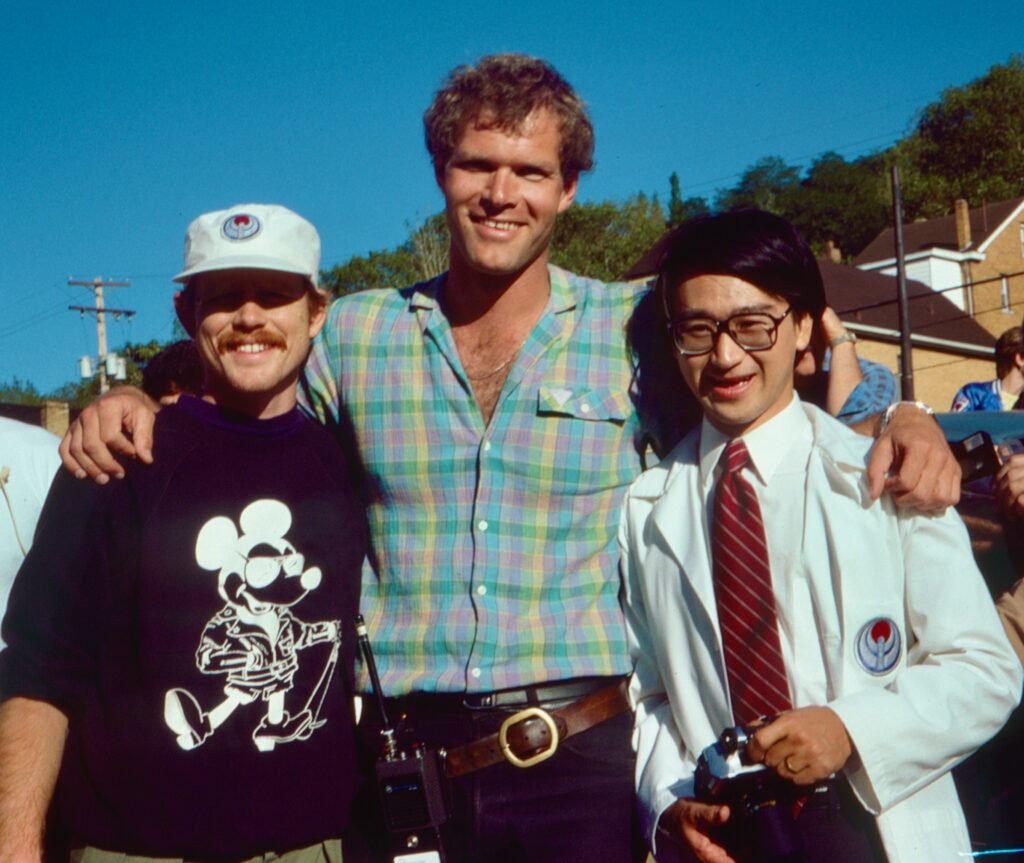

“Counter to everything you read about Hollywood, no other endeavor in the United States is more hierarchical and more demanding of respect for authority. Only the military. My Hollywood is the group that makes the show.” (Bruce Carter, center, poses with famed director Ron Howard (left), and actor Gedde Watanabe on the set of “Gung Ho.”)

— Bruce Carter

Carter started on the ground floor, perhaps even the basement, working as a second assistant director on a 1986 Roger Corman-produced B-movie Sorority House Massacre. “I was great friends with the killer,” he says. “We hung out a lot.”

His career got a boost when he was accepted to the Directors Guild of America apprentice program in Los Angeles, a rigorous, prestigious experience that gave him on-the-job training on shows that ran the gamut – detective series, science fiction and more.

His career took off after that, and he worked on projects including Steve Martin’s Father of the Bride movies, the HBO horror anthology Tales From the Crypt and many more. All the while, the organizational skills and curiosity that he honed as an Earlham student and later as a geologist served him well.

“I was able to work on things that are interesting,” Carter says. “Every show I work on, I have to learn something.”

No business like show business

As he moved up in the production food chain to the positions of production manager and line producer, he learned how to navigate the Hollywood hierarchy and help manage multi-million dollar budgets and 100-plus person crews. He enjoyed the constant problem-solving nature of the work and prided himself on treating the people on the set well. Over the course of a day, he might interact with the network, the studios, the creative team and the crew members that get it all done.

Greenwalt, the writer, worked with Carter for years while shooting the fantasy police procedural Grimm on location in Portland, Oregon. “Bruce had a very important job. It’s a very broad skillset. You’ve got to know what everybody is doing. The hours can be brutal,” he says. “Line producing is where art and commerce meet. Let’s not forget, it’s a big show business. We all want to have success, and we all want to make the very best thing we can.”

The way Carter cares about people on his team sets him apart from other producers, says Sara Beko, a producer and stunt professional who used to work as his assistant.

“He’s just a great guy to work for, and he’s really good at what he does. He’s really good at problem solving, and also identifying things that will become problems,” she says. “He’s good at saving the studios money in places where they can, but also really good at being an advocate for the crew, which is super important. Just a great overall all-around guy.”

Having gained mastery over the demands of the movie set, Carter has grappled with challenges of a different sort. In 2021, he was involved in a car accident caused by a hit-and-run driver.

Over the course of the next year, injuries from the accident worsened, until he finally was unable to walk and also unable to continue working. It has been a dark moment, but he is starting to glimpse the light once more. He’s had both hips replaced, and, as of late spring this year, is finally able to walk again after two years of immobility. “If there’s a bright side, it’s that the past two years have probably been the worst for employment in the history of cinema,” Carter says.

Although he has been on hiatus for the last few years, he hopes to get back into the mix soon.

“Every show is going to be different, with a different set of problems, and every day is different. Sometimes amazingly different,” Carter says. “That’s why I love this business.”

After all, there’s no business like show business.

Story by Abigail Curtis. Photos courtesy of Bruce Carter